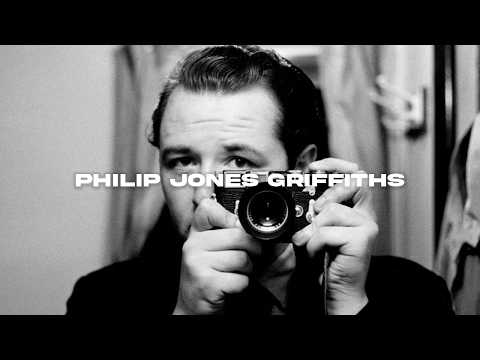

Many conflict photographers make compelling work that shapes public opinion on the wars they document. Philip Jones Griffiths did this not only through his images, but also through the deeply considered writing that accompanied them. As the longest-serving president of Magnum Photos, he influenced the worlds of street and documentary photography in lasting ways.

Philip Jones Griffiths was born in Wales in 1936. He began photographing at fourteen, and his interest deepened after discovering the British photojournalism magazine Picture Post and joining the Rhyl Camera Club. His early work included wedding photography, local landscapes, and shooting at a holiday camp. Looking back, he said, “I got all that beautiful landscape stuff

out of the way in North Wales and was ready for the rest of the world.”

In 1959, Griffiths moved to Liverpool to study pharmacy, freelancing for The Sunday Times, The Guardian, and The Observer. By 1961, he was a full-time photographer for The Guardian, covering Northern Ireland, the war in Algeria, and events in Zambia, Israel, and Cambodia—work that set the trajectory of his career.

Britain in the 50s & 60s

Griffiths’ photographs from this period, later exhibited as Middle Years, reflected his drive to escape the boredom he feared in Wales. “My only fear in life was and is boredom… I became aware that photographers ran around the world, like Samurai or Zen warriors with a Leica… showing the world to people in a way that enabled them to make changes.” He learned to seek unconventional “tangential connections” to big stories, a strategy that got him noticed by editors.

Much of his work at the time was shot on a British-made Rolleiflex. Influenced by Cartier-Bresson, Griffiths refused to crop his images, focusing instead on perfect framing in-camera. He developed the ability to blend into a scene—sometimes feigning yawns—before seizing the decisive moment. These skills brought striking images of British streets, protests, cultural events, and even The Beatles.

Out to the World

Griffiths eventually photographed in over 140 countries. One of his first major assignments abroad was in Algeria, where France’s war for control forced civilians into camps. Griffiths was the first to photograph these camps, turning rumor into visual proof and cementing his role as a conflict photojournalist.

Vietnam

While Griffiths also worked in Zambia and Israel, his defining body of work came from Vietnam. Financing his early Vietnam coverage with a photo of Jackie Kennedy in Phnom Penh, he went on to photograph the war from 1966 to 1970.

His 1971 book Vietnam Inc. combined photographs with sharp, empathetic writing. Magnum describes it as “crucial in changing public attitudes in the United States… helping to put an end to the Vietnam War.” Noam Chomsky later said, “If anybody in Washington had read that book, we wouldn’t have had these wars in Iraq or Afghanistan.”

In Vietnam Inc., Griffiths detailed how war shattered rural life. Rice farming, central to Vietnamese culture and identity, was disrupted, replaced with imported American rice that locals despised. In “Why We’re There,” he likened U.S. attitudes toward Vietnam to English colonial superiority over Wales.

He documented the devastation of “Search and Destroy” missions, the disintegration of village life, and the rise of prostitution and displacement as survival strategies. Griffiths described Tet 1968 as the moment the war’s logic collapsed—when cities, thought to be safe havens, came under the same bombing as the countryside.

Reflecting on the war, he wrote: “For more than ten years the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth tried everything short of nuclear weapons to defeat… poor rice farmers. And they failed. America had the smart bombs but the Vietnamese had the smart minds.”

Agent Orange

In later years, Griffiths returned to Vietnam to document the long-term effects of Agent Orange, focusing on children and grandchildren of survivors. He countered the short-term nature of most war reporting, showing that the consequences of conflict endure long after headlines fade.

With today’s conflicts and cycles of violence echoing the past, Griffiths’ work is a reminder that documentary photography—when paired with truth-driven writing—can challenge narratives, shift public opinion, and push for change.